Data URI images: Are we there yet?

Essay

What are data URIs anyway?

This question probably needs to be answered before we explore the pros and cons of data URI images. In a nutshell: Data URIs provide a way to embed data instead of referencing to it, hence there is no longer the need for the referenced file. Confused? Read about the data URI scheme on Wikipedia.

The simplest of all images

I’ve been making websites for more than a decade now. In the beginning, when it was all Netscape Navigator and no CSS, you needed tables and images, and—pardon my French—you needed a shitload of them. But almost all these image tags referred to the same GIF file. The file contained not more than one transparent pixel, and that pixel would get stretched to whatever width and/or height was needed. As is had been transparent, it never got distorted. Its sole purpose was to make sure that the surrounding table cells expanded to whatever size the image had been stretched to. Did I already mention that back then we stretched the hell out of this poor pixel?

Be that as it may, if we send said transparent pixel through some serious base64 encoding, we get a data URI. Put this URI in the src attribute of an image tag and it looks something like this:

<img src="data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAALsEBLsEBCH5BAEKAAEALAAAAAABAAEAAAICTAEAOw==">Gesundheit! Looks like someone sneezed at our markup. We’ll get back to this syntax, but first let’s find out why the web isn’t already swarming with data URIs.

Internet Explorer

As with almost anything in the world of web browsing, the reason why data URIs haven’t really taken off yet is found in the lack of support in the still dominating browser. Internet Explorer 8 supports the data URI scheme in part. With IE9, data URIs become much more usable because there are fewer restrictions.

Right, IE9. We are not really there. Even Microsoft would like to see IE9 download figures go through the roof, but it is usually users of other browsers who upgrade more frequently. While there might be many cases where not upgrading to newer versions of IE is simply caused by a lack of knowledge on part of the user, there is more to it: On a corporate computer it is usually not yours to decide on when to upgrade, and on computers still running Windows XP it is not even possible. But I digress.

So what about data URI images? Do we once again have to sit back and wait for ginormous changes in browser usage? The answer is going to be »No«, as you will see right after the following example.

How to use data URI images

I promised we’ll get back on the syntax, and here it is. But this time, instead of just one transparent pixel we’ll use an image we can actually see.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<style>

p {

background: url(data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhDAAYAOMOACaRnyeSoCeToCeToSeVoyiWpCynti+xwTCzwzK9zjbM3jfO4TjQ4zjR4////////yH5BAEKAA8ALAAAAAAMABgAAAQp8MlJ62OALPuMKESAVEdhmkIiKcPpFkDTvu5M33iu73zv/8CgcEgcRgAAOw==)

repeat-x bottom #f5e9bd;

width: 170px; margin: 2em; padding: 20px 20px 40px;

color: #595444; font-style: italic;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

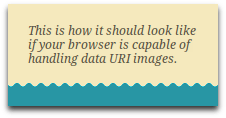

<p>This is how it should look like if your browser is capable of handling data URI images.</p>

</body>

</html>

This time the data URI is part of the CSS, or more specifically, the background property. In the example I’ve taken the liberty not to use an external CSS file, so you can copy the whole code, paste it into an HTML file and check if the result looks anything like that picture.

Why and when to use data URI images

Why indeed? With all the old versions of Internet Explorer still around you end up with twice the work. Data URIs for the capable browsers, and additional code to tell IE7 (in some cases even IE8) where to find the external image files instead. And it gets worse, because more data has to transferred to the user. Even if a base64 encoded data URI is compressed before it is transmitted, it is never going to be as small as the actual image file.

So forget about it? Not yet. Below are some personal thoughts on when to actually use data URI images.

Small images

Yes. The repeating background tile in the example above is a perfect candidate. Despite the increase in size we should experience a performance gain thanks to all the HTTP requests we save on all the small images. While we’re at it: Always choose the smallest file format. This applies for images in general, but it is even more important with data URIs. I was going to use a PNG file for my example, but it turned out the GIF counterpart had almost half the size.

Not so small images

In almost all cases: No. But you’ll have to take a second look if you are designing a secure site. To quote Wikipedia:

When browsing a secure HTTPS website, web browsers commonly require that all elements of a web page be downloaded over secure connections, or the user will be notified of reduced security due to a mixture of secure and insecure elements. HTTPS requests have significant overhead over common HTTP requests, so embedding data in data URIs may improve speed in this case.

CSS sprites

Maybe. If you switch to a data URI, you probably no longer need the sprite. Instead, split it into the original small files, that way you can also get rid of the background positioning. On the other hand, every binary image comes with a header, that’s why even something as small as one transparent pixel in a GIF file has at least 43 bytes. Splitting into many small files means many of these headers. And these headers are going to be encoded too. So a good mix could be necessary, say a couple of smaller sprites instead of one large one. There is no easy answer.